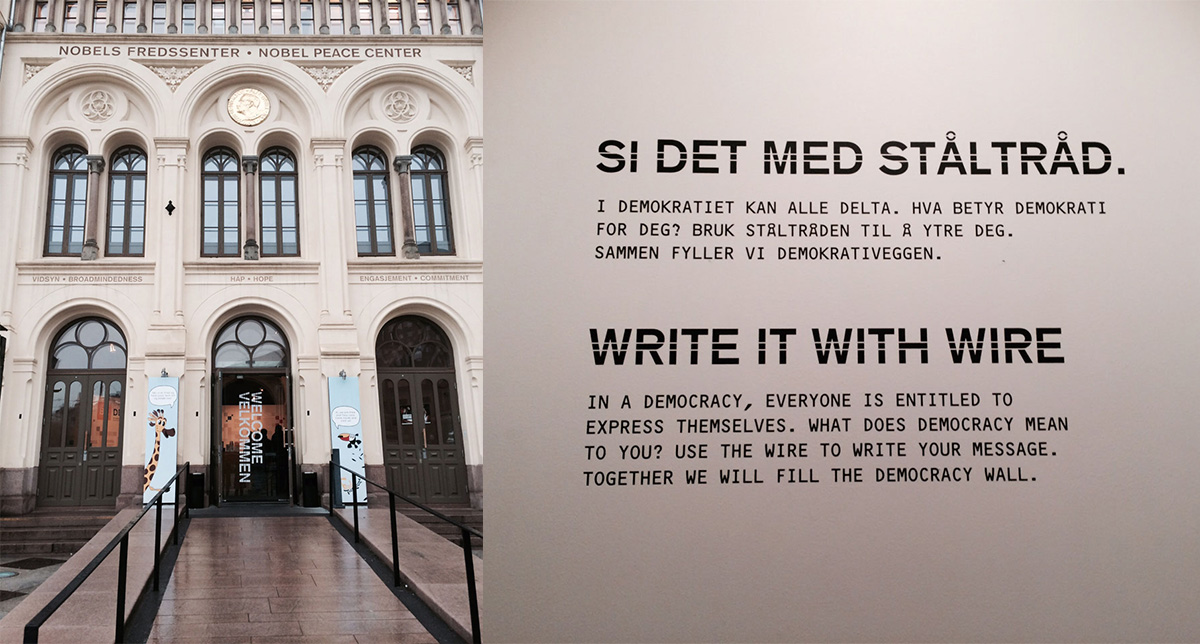

One space in particular captured my attention: a white room with a simple invitation—”Write it with wire. In a democracy, everyone is entitled to express themselves. What does democracy mean to you? Use the wire to write your message. Together we will fill the democracy wall.”

Inside, colourful wire pipe-cleaner expressions filled every corner. Shapes, words, letters, and symbols hung from above, surrounding a single table where visitors could quietly craft their own interpretation of democracy. They could attach their creation to others’ contributions or find their own space on the wall. Sitting at that table, surrounded by expressions from people of diverse backgrounds and perspectives from around the world, I felt an overwhelming sense of collective community. This quiet yet powerful moment transformed my understanding of design’s possibilities and how we can meaningfully engage people.

Photo: Karen Oikonen, Nobel Peace Centre, Oslo Norway (2014)

From Inspiration to Practice

A few years later at SE Health, I had the opportunity to reimagine how we might share findings from an existing research project in a more engaging, interactive way. Drawing inspiration from my Oslo experience, I explored participatory museum exhibits, installations, and participatory art. Discovering Candy Chang’s Before I Die and Confessions installations and Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree and My Mommy is Beautiful installations was pivotal. These artists created work that invited public participation, building art through community contributions. As installations overflowed with deeply personal perspectives and experiences, I wondered: “What insights might emerge from synthesizing all this data? What could it reveal about people’s worldviews?”

This exploration led to The Reflection Room at SE Health—my first participatory installation at a conference in 2018. After leaving SE Health, I pursued my passion for exploring the intersection of participatory art, design, and end-of-life conversations through Death, Dying and Design, a side project with Kate Hale Wilkes, and additional public installations with Sarina Isenberg at the Bruyère Health Institute in Ottawa. These projects helped me see that participatory installations are powerful as both an approach to engagement as well as a research method, as the collected inputs become valuable data that deepens our understanding of human experiences and community perspectives.

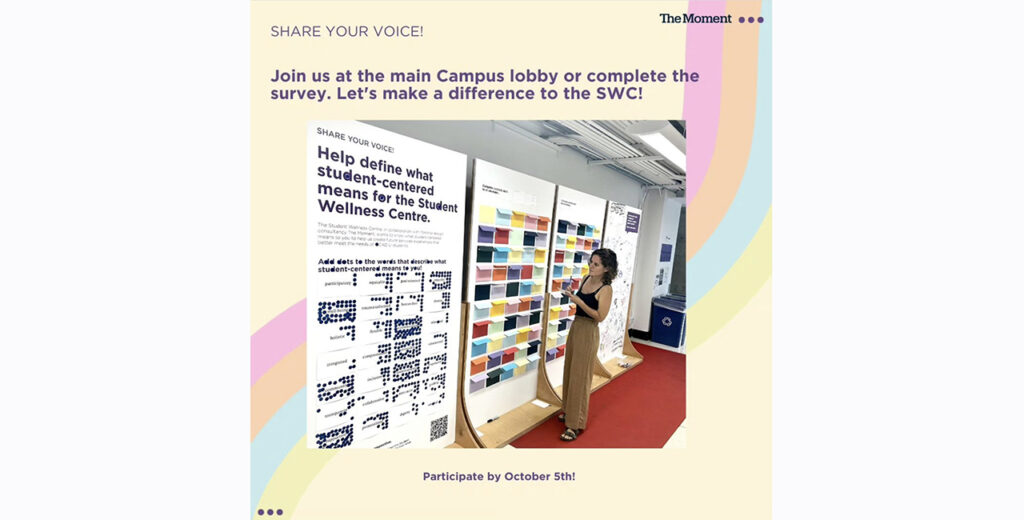

Recently, I led a Service Design Review project at The Moment with OCAD University’s Student Wellness Centre. Given the SWC team’s commitment to deep student engagement, we integrated two participatory installations into our overall approach to student engagement and research, creating spaces where students could share their perspectives, challenges, hopes, and experiences—prioritizing student voices rather than positioning the project team as experts.

Photo: instagram @ocadustudentwellness

Why participatory approaches matter

This decade-long journey has revealed key insights about what makes participatory installations valuable for research and consultation and lead to increased participation:

- The act of participation has value in and of itself. Participatory installations offer unique opportunities to share perspectives while seeing our experiences in the context of others. When exploring vulnerable topics like democracy, death and dying, and mental health, seeing your experience as part of a collective can signal “it’s not just me”—providing moments where people feel less alone. Unlike some research methods where experiences are often shared in isolation, participatory installations enable collective creation, emphasizing human connection over transactional exchanges.

- Low barrier to participation and autonomy. Participatory installations offer a welcoming space where people can share anonymously—no names, emails, or identifiers needed. The goal is to design an installation so that people can participate without depending on facilitation. Having project team and community members host for a few hours daily provides connection opportunities while maintaining participant autonomy. Whether someone wants to write a single word or a lengthy reflection, spend five minutes or an hour, drop by at noon or midnight while studying on campus, the choice is theirs. By creating this flexible, pressure-free environment, we reach voices that might otherwise go unheard through more commonly used research approaches.

- The creative experience enriches participation. Installations transform research into an engaging visual and tactile experience. By designing colourful, inviting spaces with multiple ways to contribute—from stickers to private reflection spots—we create environments for participation that feel welcoming and accessible. During the Student Wellness Centre project, students appreciated sharing perspectives through creative expression in familiar campus spaces, shifting away from expert-driven formats to create value for both researchers and participants.

- Adaptable methods enhance depth of learning. Participatory installations adapt flexibly to each community’s needs and goals. They can surface key topics during discovery that inform subsequent interviews or co-design sessions. When run parallel to surveys, they offer interactive alternatives to increase engagement—whether through interactive components such as weaving string, adding stickers, adding cards to an envelope wall, or dot voting—to explore the same questions. The collective input can guide deeper exploration while providing creative ways to validate ideas and prototypes later in the design process.

Making Space for Every Voice

Human beings are natural storytellers. Providing diverse ways for people to share their perspectives, experiences, challenges, hopes, and expectations is essential in research and community engagement. While interviews and surveys have their place, understanding human experience deeply requires approaches that offer different ways for people to tell their story in addition to these common methods. This is especially crucial when exploring vulnerable topics like student mental health, where meaningful value exchange and ensuring participants feel heard is vital. Participatory installations offer this deeper connection while helping reduce stigma and foster community bonds by creating space on campus for engagement that is both visible and accessible to all.

Reach out if you’re interested in learning more about how participatory installations can enrich student engagement. I’d be happy to share The Principles for Co-design with Students on Campus Canvas. Recently presented at the Centre for Innovation in Campus Mental Health Conference, this resource includes six principles, including Participatory—which explores reducing barriers and meeting students where they are.